How Has Plagiarism Typically Been Defined?

Plagiarism has traditionally been defined as:

- Theft of Ideas: Presenting someone else’s original thoughts, theories, or concepts as your own.

- Theft of Words: Copying someone else’s written or spoken words without proper quotation or acknowledgment.

- Failure to Cite: Not properly crediting sources when quoting, paraphrasing, or summarizing another’s work.

Plagiarism can be intentional or accidental—whether it’s deliberate copying or carelessness, like not knowing citation rules. While the severity of offenses may vary, plagiarism invariably carries consequences in both academic and professional realms. A prominent example of these consequences unfolded in early 2024 with the resignation of Claudine Gay, Harvard University’s president. Gay faced mounting allegations of plagiarism in her scholarly work, spanning her entire academic career. Despite initial support from Harvard’s governing board, the persistent accusations and scrutiny ultimately led to her resignation, demonstrating the serious repercussions of alleged ethical breaches in academia.

How Are AI Tools Challenging Traditional Definitions of Plagiarism?

Historically, in the U.S. and the Western world, the unauthorized use or theft of someone else’s words and ideas without proper attribution is a serious academic, ethical, and legal offense. Plagiarism in academic contexts, especially intentional plagiarism as opposed to confusion on the part of the student about citation conventions, typically warrants an FF on a student’s academic transcript. In workplace contexts, plagiarism may result in termination, economic, and legal consequences.

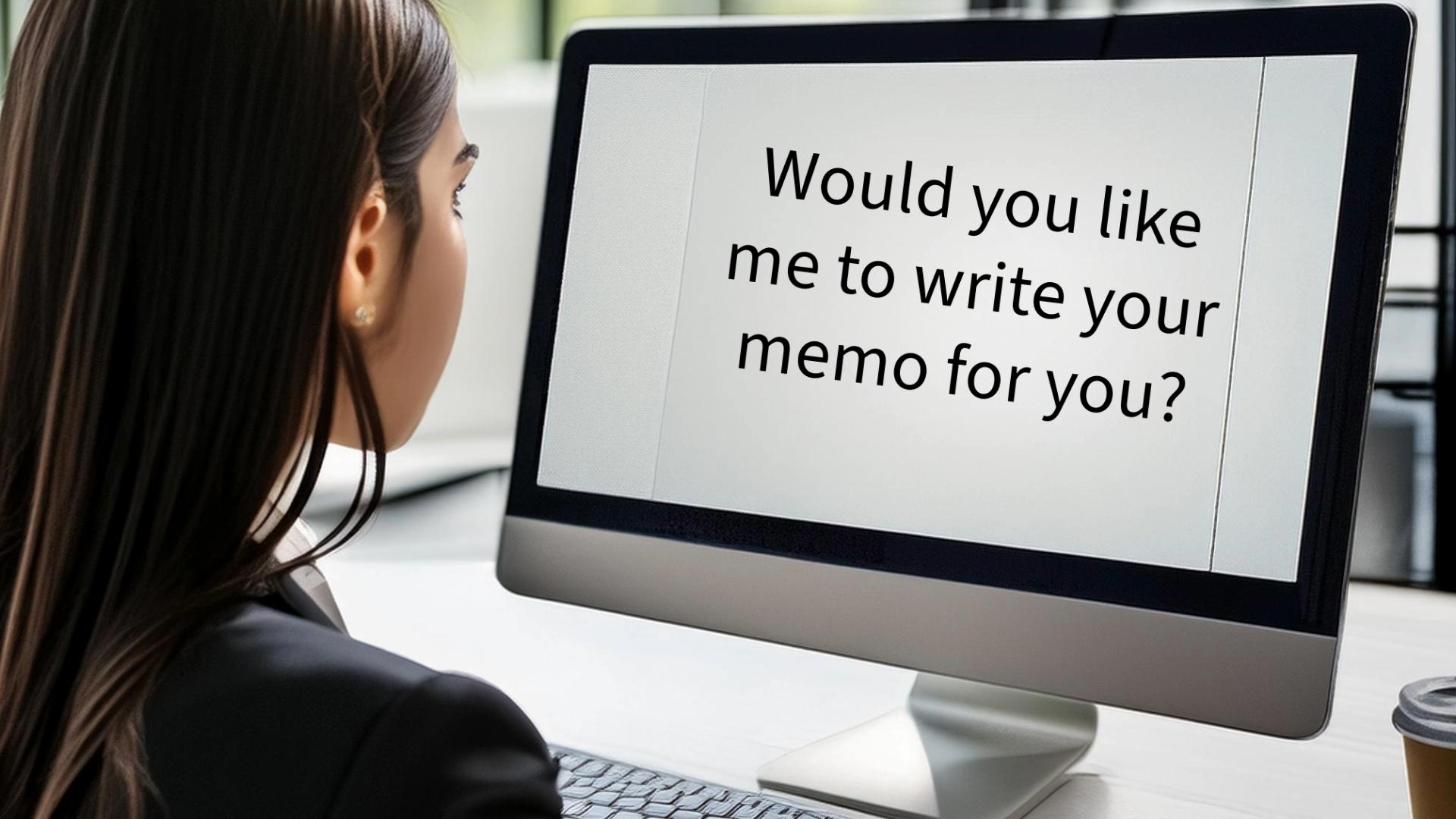

However, thanks to the meteoric rise of GAI (Generative Artificial Intelligence) tools, traditional models of composing or concepts of plagiarism, authorship, copyright, and attribution are under assault. Typical discourse conventions associated with plagiarism and academic integrity fail to account for how some writers are composing with AI tools. Yes, it’s clearly plagiarism when a writer prompts an AI tool to draft an essay or memo for them and then submits that work for school and work assignments.

Yet, is it plagiarism when a writer works with AI to facilitate (1) rhetorical processes (especially rhetorical analysis and rhetorical reasoning); (2) composing processes (e.g., prewriting, inventing, drafting, collaborating, researching, planning, organizing, designing, rereading, revising, editing, proofreading, sharing or publishing ); (3) the development of an appropriate writing style given the rhetorical situation; and (4) editing for style and clarity (e.g., brevity, coherence, flow, inclusivity, simplicity, and unity).

How Are AI Tools Changing the Way We Write?

The boundaries of plagiarism blur when writers engage in ongoing dialogues with AI tools.

Rhetorical Reasoning

- Is it plagiarism when a writer trains AI systems to understand their rhetorical situation, exploring exigency, audience, and potential rhetorical moves. If a writer depends on AI to generate rhetorical strategies, is it still their original reasoning? At what point does reliance on AI become a substitution for critical thinking?

Prewriting & Invention

- Is it plagiarism when writers ask Semantic Scholar, Consensus, or Consensus to summarize research on a topic, perhaps writing annotated bibliographies?

Researching

- Is it plagiarism when writers use LitMaps or Research Rabbit to visualize scholarly networks of papers? What if they ask the AI to identify canonical texts, the evolution of scholarly conversations, and research gaps?

Planning

- Is it plagiarism when writers develop or use a chatbot to motivate themselves to engage in daily writing or to remind them of their writing schedule? The AI tool might send personalized prompts, offer encouragement, and help set daily or weekly writing goals, effectively acting as a virtual writing coach. Does relying on AI for motivation and time management impact the writer’s autonomy in the planning process? If the AI provides specific prompts or influences the direction of the writing, should this involvement be acknowledged? Where is the boundary between logistical support and creative input when using AI in planning?

Designing

- Is it plagiarism if a writer asks AI systems to plan headings for their documents, to evaluate whether the thesis is consistent and clear throughout the paper, to revise an inductive draft into a deductive argument? If the overall plan or structure is significantly influenced by AI, does this diminish the writer’s ownership of their work? Should the use of AI in planning be disclosed?

Organizing

- Is it plagiarism if a writer uses AI tools to enhance the visual aspects of their work, incorporating concepts from design principles, elements of art, and information design. What if they employ AI software to generate color schemes (Color Theory), select appropriate typography, create infographics, or produce data visualizations to complement their writing. How does the integration of AI in design affect issues of authorship and potential plagiarism, especially when AI-generated visuals are a significant part of the communication?

Rereading

- Is it plagiarism if a writer asks AI tools to read their drafts aloud to catch errors, awkward phrases, or soft spots? What if they use AI to engage in sentiment analysis or to compare drafts? Should these types of AI assistance be acknowledged, or do they dilute the writer’s engagement with their own text?

Revising

- Is it plagiarism if a writer asks the AI to check on whether or not their ideas need to be developed, reorganized, or rewritten? If AI-driven revisions substantially alter the original text, does this affect authorship? Is there an ethical obligation to disclose the extent of AI involvement in the revision process?

Editing & Proofreading

- Is it plagiarism if a writer asks an AI system to check their style (e.g., brevity, coherence, flow, inclusivity, simplicity, and unity), syntax, and punctuation? When AI makes significant edits, at what point does the text cease to be solely the writer’s work? Should the writer acknowledge AI’s role in polishing the document?

How Are Faculty Responding to AI?

The emergence of AI tools — such as ChatGPT, Perplexity, or Claude — signifies not just “a paradigm shift” in the Kuhnian sense but an “epochal shift” — a monumental transformation in the fabric of plagiarism, authority, and intellectual property.

In response to the rise of AI, faculty members are unsure whether to permit or prohibit AI usage for school assignments. Lance Eaton (2024) has been collecting faculty members’ AI-policy statements since 2023. Eaton’s corpus of AI policy statements from faculty across disciplines and institutions demonstrates enormous disparities in faculty members’ acceptance of AI in student work: some faculty permit AI solely for invention, research or revision; others reject AI usage altogether. STEM and business faculty tend to permit AI usage whereas humanities faculty are more likely to reject AI usage, considering it to be academically dishonest. Across disciplines, faculty provide disparate citation policies: some faculty require every AI-generated sentence to be cited; others permit students to write a general note about their dialogs with chatbots; others call for students to estimate AI’s contribution as a percentage of involvement with GAI tools.

Technorhetoricans assure us this is not a new story (Dobrin 2002). Writing, a technology, is always under constant evolution. As a species, we are always looking for new ways to express ourselves. We are quick to adopt technologies, processes, and writing spaces/media that make it easier for us to accomplish the tasks we want to accomplish (Baron 2009). Consider, for example, the use of hyperlinks at Writing Commons: these hyperlinks enable authors to layer knowledge hyper textually so if readers don’t understand a concept, they can click and learn more about it.

The affordances and constraints of today’s hardware and software are altering the human experience, remediating our ways of researching and solving problems, interpreting information, and thinking/composing/creating — and challenging our conception of plagiarism and the writing process. To put it more simply, technologies shape culture. Consider, for example, how the printing press threatened the authority of the Catholic Church: it introduced counter narratives. It facilitated the spread of ideas, hermeneutics, textual-methods, empirical research methods — and the overall emergence of the conversation of humankind (Bolter 2001).

As of 2024, many faculty believe GAI tools violate academic integrity, discourse conventions, and empower plagiarism. For these faculty, AI reflects the greatest theft of intellectual property of all time.

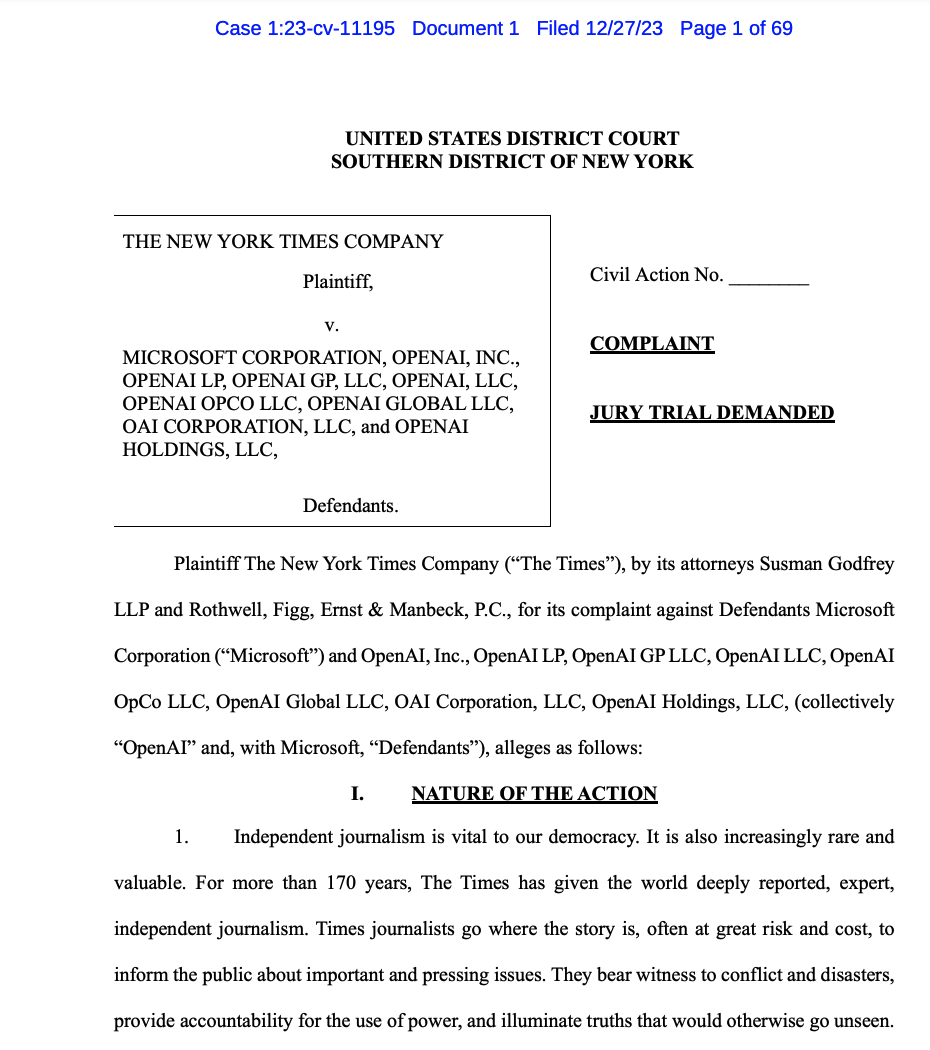

In 2022, OpenAI released GPT-3, their groundbreaking language model that could generate human-like text. But this technological feat also sparked heated controversy. GPT-3 was trained on a colossal dataset of over 300 billion words, comprising millions of copyrighted books, articles, websites and other creative works, which were compiled without explicit permission from rights holders. While OpenAI argued this data ingestion fell under fair use provisions, The New York Times and the Writers Guild of America asserts it constitutes copyright violation and intellectual property theft on a massive scale.

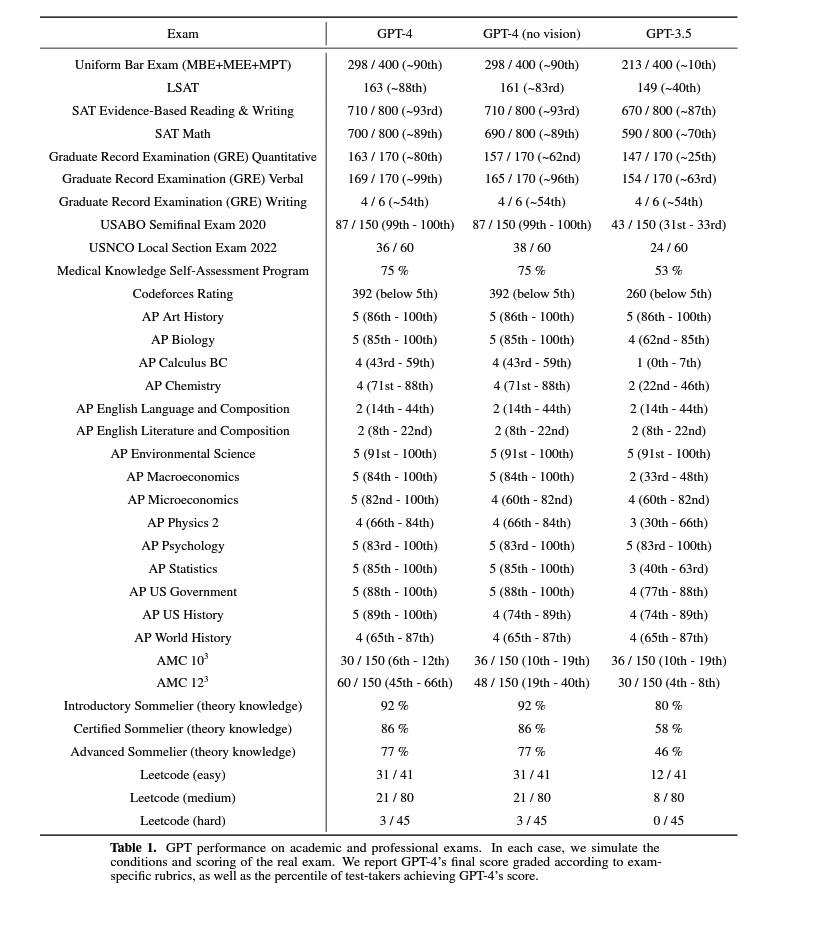

Lawsuits and concerns about copyright and aside, OpenAI’s move proved pioneering. On many standardized tests, the next iteration of ChatGPT scored in the top 90% on some important, life-determining tests, such as the SAT or Bar Exam:

As a result of the success of OpenAI, Claude, Perplexity, other AI startups soon followed suit by releasing their own large language models trained on corpora of open and copyrighted data. Presently, new AI models and new iterations of past AI models are announced on a nearly daily basis.

| AI Tool | Description |

|---|---|

| Ask Your PDF | Allows users to interact with PDF documents through conversation, simplifying data retrieval and analysis. |

| ChatPDF | Upload a PDF and start asking questions to make reading journal articles faster and easier. |

| Consensus | Analyzes scientific documents to extract key points and data, aiding faster literature reviews. |

| Elicit | AI research assistant that searches, summarizes, and extracts data from over 125 million papers. |

| Inciteful | Helps researchers discover and analyze academic papers and trends through visual maps connecting citations/topics. |

| Ithaka GenAI Tracker | A resource for tracking generative AI tools marketed to postsecondary faculty and students. |

| Keenious | Finds research relevant to any text by allowing AI to analyze documents and explore results. |

| LitMaps | Visualizes relationships between academic papers to track developments and identify key influencers. |

| Perplexity | AI-powered search tool for academic research, summarizing key findings but potentially including paper mills. |

| ResearchRabbit | Visualizes scholarly networks of papers and suggests related articles, like Spotify for research papers. |

| SciSpace | Provides access to over 200 million research papers and summarizes answers to research questions. |

| Scite AI | Uses deep learning to evaluate scientific papers and provides ‘Smart Citations’ indicating support or contradiction. |

| Semantic Scholar | Indexes over 200 million research papers and provides related papers, background citations, methods, etc. |

| Undermind | Uses Semantic Scholar to provide accurate results for academic research topics. |

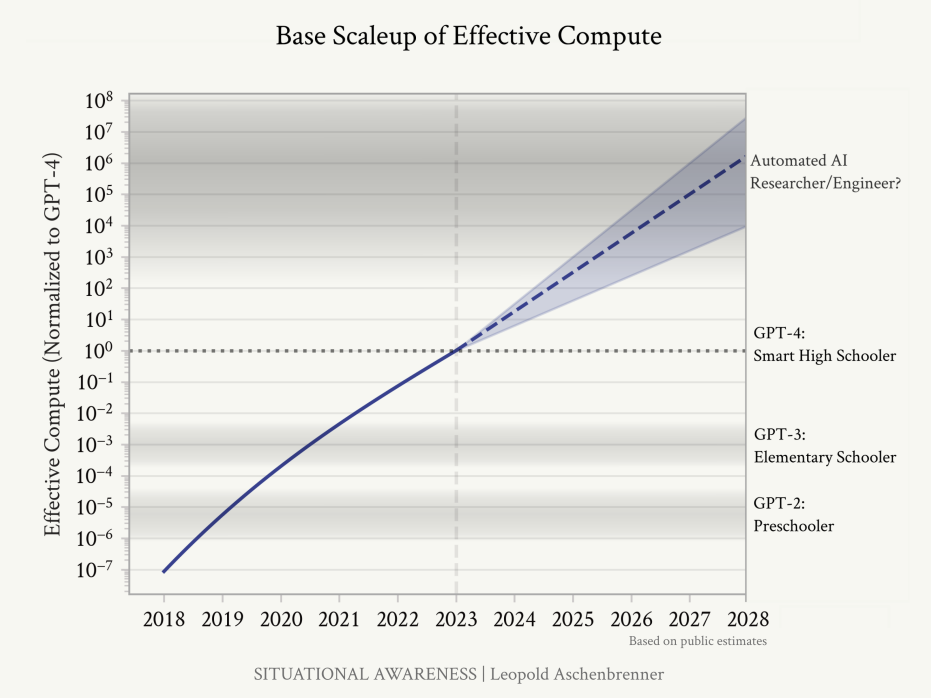

Admittedly, many of these tools are in their infancy. They are like human babies, just learning to walk and talk. Yet it’s clear they have a sharp learning curve. Some predictions suggest they will reach superintelligence by 2028 — a status where they are smarter than humans and will be engaging in their own independent research. If this happens — if AI tools can be smarter than Ph.D.s in a subject, capable of outputting in any language, we’ve got to wonder how society will reimagine the role of authorship and copyright.

In summary, faculty are troubled by the ethical foundations of GAI tools. They are troubled that Taylor & Francis, a major academic publisher, recently sold (for $75m) access to millions of scholarly articles to AI companies without explicit author consent. They dislike grading student work that is solely written by AI. And they worry that when students have AI do their writing for them that they will not develop their critical thinking competencies or abilities to express themselves.

How Are APA and MLA Citation Rules Overlooking the Realities of AI-Assisted Writing?

To summarize, the capabilities of GAI tools complicate traditional conventions for attributing and citing sources:

- Hybrid Writing: The final product of human-AI collaboration often results in a blend of human and machine inputs. This hybrid writing process, where a writer uses multiple AI tools to refine a single sentence or paragraph, challenges the line between human authorship and AI contribution.

- Blurred Lines Between Paraphrasing and Original Content: AI-generated text often falls into a gray area. It’s not directly copied from any single source, yet it’s not entirely original either. Tools like ChatGPT create content based on patterns in existing data, which challenges our understanding of what constitutes acceptable paraphrasing and summarizing versus plagiarism.

- Attribution Challenges: Many AI tools don’t inherently provide citations for the information they use. Because the LLMs may include false information and papers from papermills, users may unknowingly present AI-generated content that includes misinformation, raising questions about how to properly attribute this information.

- Style Imitation: While mimicking an author’s style has been considered by some to be a form of plagiarism, AI tools can now generate content in specific styles or voices. Many AI tools can produce text in the style of famous writers, further complicating the definition of plagiarism in terms of style appropriation.

Regardless of these complexities, citation styles such as MLA and APA call for writers to cite all work drafted by AI:

- APA 7th Edition (2023): Recommends citing AI tools as the author, with in-text citations and references adapted from the reference template for software.

- MLA 9th Edition (2024) Suggests citing AI-generated content whenever it is paraphrased, quoted, or incorporated into one’s work, including information about the prompt in the “Title of Source” element if not mentioned in the text.

While these guidelines provide a framework, they are often impractical in real-world writing contexts. Here are several challenges with these citation conventions:

- Dynamic Nature of AI Interactions: Users often engage in iterative dialogues with AI tools, constantly refining content. This dynamic process, where a writer revises content in an ongoing dialog with AI, complicates the determination of what should be cited and how to cite three or four AI tools that helped a writer refine a metaphor, voice, tone, persona — or whatnot. In response, some teachers ask students to submit chat logs with their assignments. There are apps freely available to allow students to record their composing sessions and then freely share their recordings via gDocs or a file upload. Yet teachers do not have the time to review hundreds of pages of dialogs with dozens of AI tools. As a result, students are unsure if they should cite a lengthy discussion they’ve had with a chatbot for days, even weeks, that helped them develop their thinking. As a society, we need to come with a new vision of the writing process –new set of discourse conventions that govern whether you are guilty of plagiarism if you use an AI tool for mentorship

- Multiple AI Tool Usage: In the real world, professional writers may jump between multiple tools—perhaps using ChatGPT to draft a sentence, Jasper to rewrite it for clarity, and Grammarly to edit it for grammar. How does one cite such a dynamic process? It’s unrealistic to expect writers to track each minor AI contribution, especially when several tools collaborate on revising even a single paragraph.

- AI Use Throughout the Writing Process: Current citation guidelines do not account for this broad range of use, complicating the practical application of citation rules. AI tools can be used

- throughout the rhetorical process (for rhetorical analysis of the communication situation and rhetorical reasoning)

- throughout the writing process (prewriting, inventing, drafting, collaborating, researching, planning, organizing, designing, rereading, revising, editing, proofreading, sharing or publishing)

- throughout efforts to improve voice, tone, persona or the writer’s style.

- throughout the editing process, such as checking a draft for brevity, coherence, flow, inclusivity, simplicity, and unity.

- Comparison to Human Assistance: How does using AI tools compare to receiving feedback from tutors, teachers, peers, or editors? Should these be treated equally? Existing guidelines don’t fully account for the nuances of these human vs. AI comparisons, making it difficult to establish clear citation norms.

Given this milieu, the MLA and APA citation guidelines are out of touch. Their guidelines are as helpful as saying to NASA astronauts they are expected to walk on the moon without setting foot on the moon. In response to these new writing processes, academe is in turmoil.

What Does This All Mean for Students?

Because faculty have such disparate notions about whether use of AI constitutes plagiarism, students are unsure whether or not it’s ethical to use AI to complete assignments. At this point, it appears about half of the students in the U.S. have dabbled with AI: a 2023 survey of 1600 students across 600 institutions conducted by Turnitin found 46% of students had used AI for coursework (Coffey 2023). A second 2023 survey of 1000 undergraduate and graduate students conducted by BestColleges found 56% had used AI to complete coursework (Nam 2023).

Related Resources

Citation Guide – Learn How to Cite Sources in Academic and Professional Writing

- APA – Publication Manual of the APA: 7th Edition

- Attribution — What is the Role of Attribution in Academic andn Professional Writing

- Citation Guide – Learn How to Cite Sources in Academic and Professional Writing

- Citation – How to Connect Evidence to Your Claims

- Citation & Voice – How to Distinguish Your Ideas from Your Sources

- Citation Conventions – What is the Role of Citation in Academic & Professional Writing?

- Citation Conventions – When Are Citations Required in Academic & Professional Writing?

- Paraphrasing – How to Paraphrase with Clarity & Concision

- Quotation – When & How to Use Quotes in Your Writing

- Summary – Learn How To Summarize Sources in Academic & Professional Writing

- Citation Tools

- MLA – MLA Handbook, 9th Edition

Literacy

Aschenbrenner, L. (2024, June). Situational Awareness – The Decade Ahead. Situational Awareness AI. https://situational-awareness.ai/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/situationalawareness.pdf Baron, D. (2009). A better pencil: Readers, writers, and the digital revolution. Oxford University Press. Bolter, J. D. (2001). Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Coffey, L. (2023, October 31). Students Outrunning Faculty in AI Use. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/tech-innovation/artificial-intelligence/2023/10/31/most-students-outrunning-faculty-ai-use. Dobrin, S. I. (2023). AI and writing. Broadview Press. Eaton, L. (2024). Syllabi Policies for AI Generative Tools. https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1lM6g4yveQMyWeUbEwBM6FZVxEWCLfvWDh1aWUErWWbQ/edit#gid=0 Nam, J. (2023, November 22). 56% of College Students Have Used AI on Assignments or Exams BestColleges. OpenAI (2024). GPT-4 Technical Report. https://cdn.openai.com/papers/gpt-4.pdfReferences